The Chilean Peatland Protection Law (official text), also known as “Ley Pompon”, was enacted on 26 March 2024 and published on 10 April 2024. The content can be summarised as follows: Peat extraction prohibited, Sphagnum harvesting permitted. The law is of great importance for the approximately 3.2 million hectares of Chilean peatlands, most of which are still in a natural state.

After almost 6 years in the legislative process, the peatland protection law has gone through substantial changes on the home straight. Essentially, a ban on Sphagnum harvesting, which was included in the original draft of the law, has been abandoned. This has led to much controversy between socio-ambiental organisations and politicians.

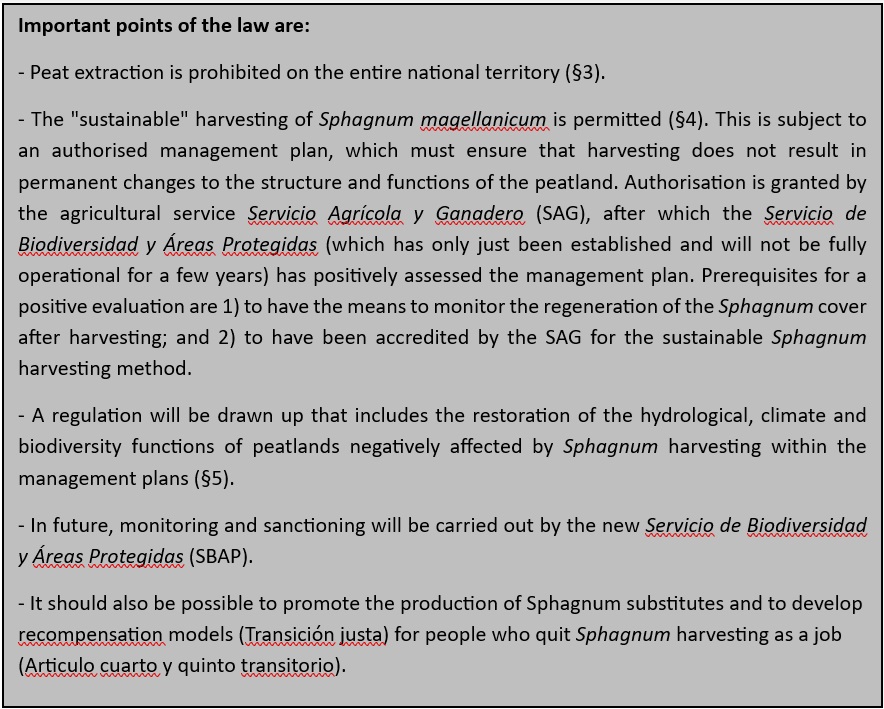

On the positive side, peatlands are no longer subject to mining law and peat can no longer be extracted. Although there has never been any significant extraction, there have already been concessions and the danger of this developing into an economic sector has now been averted.

The greatest threat to the largely untouched moorland landscapes in southern Chile is currently posed by Sphagnum harvesting (Sphagnum magellanicum), which has spread uncontrollably in recent years despite existing regulations (Decree 25).

Particularly through infrastructure development in southern Chile (e.g. wind farms for green hydrogen; infrastructure for salmon farming, expansion of power lines), previously isolated peatland complexes are being made accessible, which also entails Sphagnum harvesting. However, labelling certain forms of harvesting as “sustainable” is controversial, given the low regeneration rates of 30-60 years for 15 cm long Sphagnum strands (2.5-5 mm/yr in region of Magallanes; 4 mm/yr in region of Aysén). The main market for the mosses is Southeast Asia. A difficult to quantify but certainly large part of this work is carried out illegally or with illegal methods (number of registered harvesters; Haitian labour slaves for Sphagnum harvesting). Due to geography, ownership and, above all, a lack of monitoring resources, Sphagnum harvesting is likely to remain partially uncontrollable in the future. If harvesting had been banned, there would at least have been an effective way of preventing it, despite the many illegal harvesting activities, at least in terms of export controls. Assessing whether mosses are harvested sustainably or unsustainably will remain hard to prove in the future.

All in all, this result is a disappointment from a peatland protection perspective, considering that the original draft law (which provided for complete protection of the peatlands, including their plant cover) has already successfully passed several votes in parliament.

Unfortunately, after a campaign in favour of Sphagnum harvesting, which also used false facts and figures to convince people (e.g. there was talk of 10,000 families living from Sphagnum harvesting in the Los Lagos region alone, whereas just 1,151 officially registered Sphagnum harvesters nationwide), there was no longer a political majority in the Senate in mid-2022 to pass the bill in its original form. This also has to do with Chile’s poor economic situation following the coronavirus pandemic and the ecological government‘s reversion to extractivism. Ultimately, the current law is a negotiated compromise that was also pushed by the Ministry of the Environment, as otherwise the law would probably have died a silent death.

Resistance to this emerging compromise has been voiced primarily by civil organisations from Chiloé, an island in the south of Chile with 150,000 inhabitants, which is rich in peatlands and has a strong emphasis on small-scale agriculture. As there are no glaciers on the island, there have been such severe hydrological deficits in the summers for some time that the regional government has repeatedly declared a state of emergency (water supply by tanker, water scarcity). The obvious connection between the loss of Sphagnum cover as a water-storing element in the landscape and declining water availability has brought the issue to the attention of civil society. After the law was passed in parliament, organisations representing the affected population and agriculture wrote an open letter (letter; press report; Instagram post) calling on the president to veto the law in the last instance. At the beginning of April, however, he declared that he would not veto the bill. Previous initiatives by environmental, civil society and scientific organisations have also failed to prohibit moss harvesting (e.g. open letter from 163 organisations in favour of the Peatland Protection Law in its original form, interview with Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Hans Joosten, interview with Prof. Ing. Rodolfo Iturrsape).

This means that the chapter on peatland law in Chile is now closed after almost 6 years. How good the theoretical protection will be depends on the development of the regulation of Sphagnum harvesting (§5). After all, in a few years’ time, the SBAP will have more resources at its disposal for monitoring and sanctioning than the SAG currently has. However, the past shows that in practice, in a Chile in which the state had little priority for monitoring and sanctioning the use of natural resources despite existing laws, one should not expect too much. In the end, the new law is not a victory for the peatlands. Much more could have been achieved.